Mayweather’s Man: Trainer and Olympian Nate Jones and His Path From Jail to Boxing’s Biggest Stage

![]()

When you’re the trainer of the world’s most famous boxer, as Nate Jones is, you’ve got a few stories to tell. When you’ve made it out of one of the most infamous housing projects in America, as Nate Jones has, you’ve got a few more. And when your life has taken you from a jail cell to an Olympic podium and into the corner of arguably the greatest boxer of a generation, you could write a novel. But for now, you want to tell one specific story about when the boxer you train, Floyd Mayweather, woke up one morning in tears.

“Nate, what happened last night?” Jones recalls Mayweather asking in a panic.

Jones, unsure what Mayweather was talking about, asked him what he meant.

“Nate, I had a boxing match and I lost,” Mayweather said.

Jones pushed his wristwatch in front of Mayweather’s eyes. “Floyd, look at my watch,” he said. “That means you would have fought on Monday. The champ doesn’t fight on Monday, they fight on Saturday. You must have been dreaming.”

Mayweather just shook his head.

“It felt so real.”

Now Mayweather was gone, and Jones had no idea where he went. He yelled Floyd’s name throughout the house, with nary a response. Suddenly, the door opened, and a sweat-stained Mayweather emerged wearing a full tracksuit.

“Where have you been?” Jones asked.

“I went for a 10-mile run,” Mayweather said. “That dream felt too real.”

RELATED: Watch Floyd Mayweather’s Workout

Part of the Cabrini-Green housing projects in Chicago, which have since been torn down.

For the better part of his life, Nate Jones was the one chasing a dream, instead of helping another man chase his.

Jones grew up in Cabrini-Green, the notorious Chicago housing project, where his first experience throwing hands came in the streets. As a kid, he and his friends engaged in street fights, and Jones quickly became known as the guy who never lost.

“Anybody in my age bracket that would come to body blows with me in my projects, I would beat them,” Jones said.

They’d fight until someone got knocked down or started bleeding, or until one of them simply had enough and quit. Jones never quit.

Some of the older heads around the neighborhood took notice of Jones and the natural, albeit raw, way he threw punches. They placed him in boxing gloves and had him fight other kids that way. As he did with his bare knuckles, Jones kept on cleaning up.

“Everyone had heard about me,” Jones said. “No one wanted to fight me. They’d say, ‘There’s a young black kid that’s a good boxer. He can beat everybody.’”

None of it was technical, though. Jones had no formal boxing training, just a desire to avoid embarrassment in his tough neighborhood, where reputation was everything. Then, when he was 8 years old, Jones joined a boxing program that was starting up at Seward Park in Cabrini-Green, run by Tom O’Shea, a Chicago boxing legend. O’Shea was immediately drawn to Jones, whom he saw as a “natural” talent, and he began chipping away at the street fighting mentality that was drilled into Jones’s head.

That task would prove nearly impossible early on. Jones was terrible in the ring during his initial bouts, losing his first eight fights and threatening to quit in frustration. He would become enraged after losing, wanting to fight his opponent like he did on the streets of Chicago after the fight had already ended. O’Shea was his rock, encouraging him to stick with it as the losses piled up for the kid who had never lost a fight in his life.

Finally, something clicked. Jones remembers exactly when it happened. He was 11 years old, fighting in a national tournament. His opponent was a white kid sporting a Mohawk, and it scared Jones.

“The Mohawk scared me because I’d never seen anyone with a Mohawk before, except for Mr. T,” Jones said. “He intimidated me. But when I started fighting him and I started seeing how it was easy, that’s when I recognized that I can do this. He wasn’t as good as they were saying. That was the fight I recognized that I can really do this here. I beat that kid and really felt good.”

Jones didn’t lose again for a year and a half. He was launched on a career path that would culminate with a bronze medal in the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta—but not before he was convicted of auto theft and armed robbery. At the age if 18, he watched the 1992 Olympics from a jail cell at Western Illinois Correctional Institute. He also had a penchant for drinking, a liquid demon that floated in and out of his life like it flowed down his throat. But the ’96 Olympics was his goal, and he cleaned himself up enough to reach it.

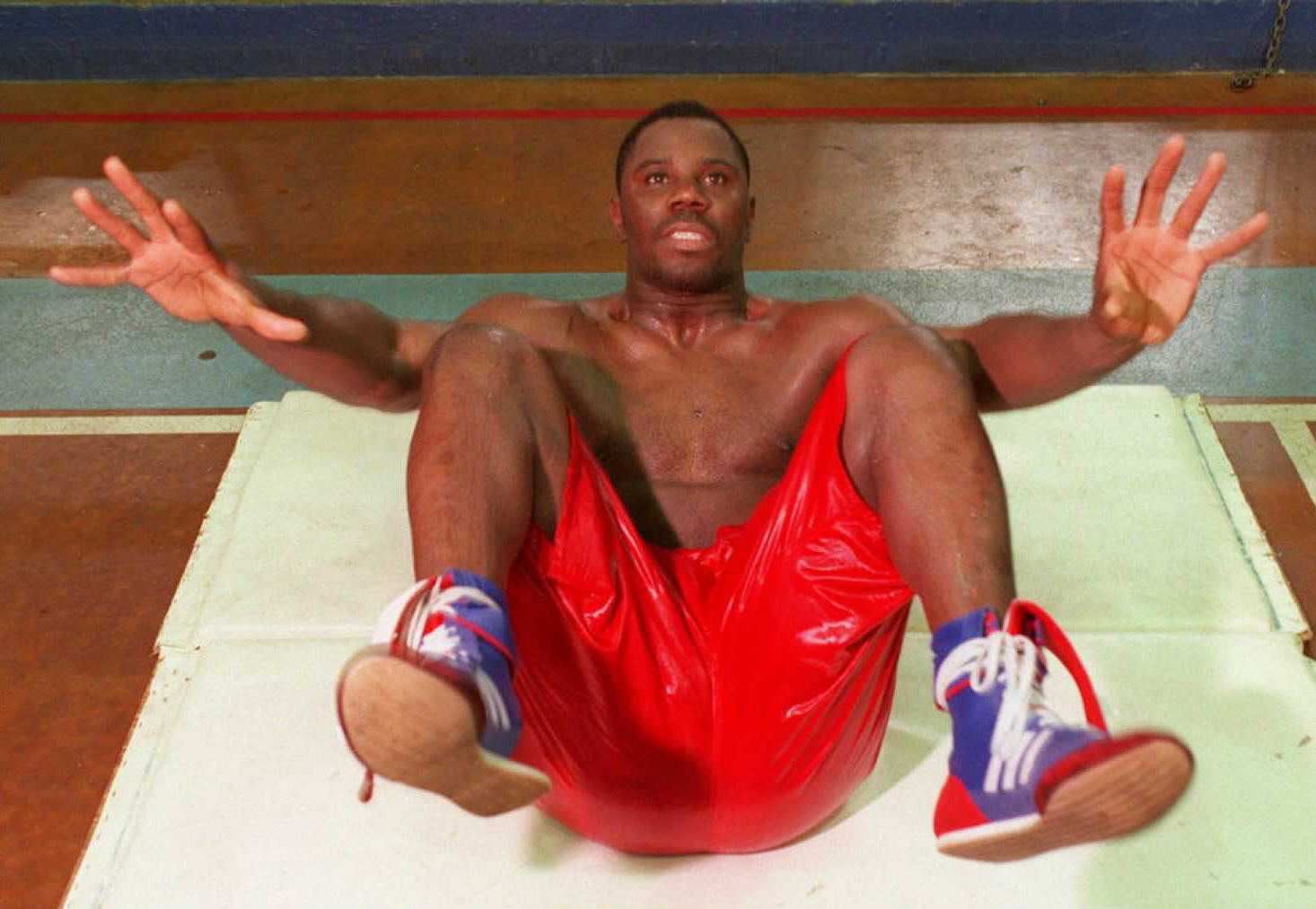

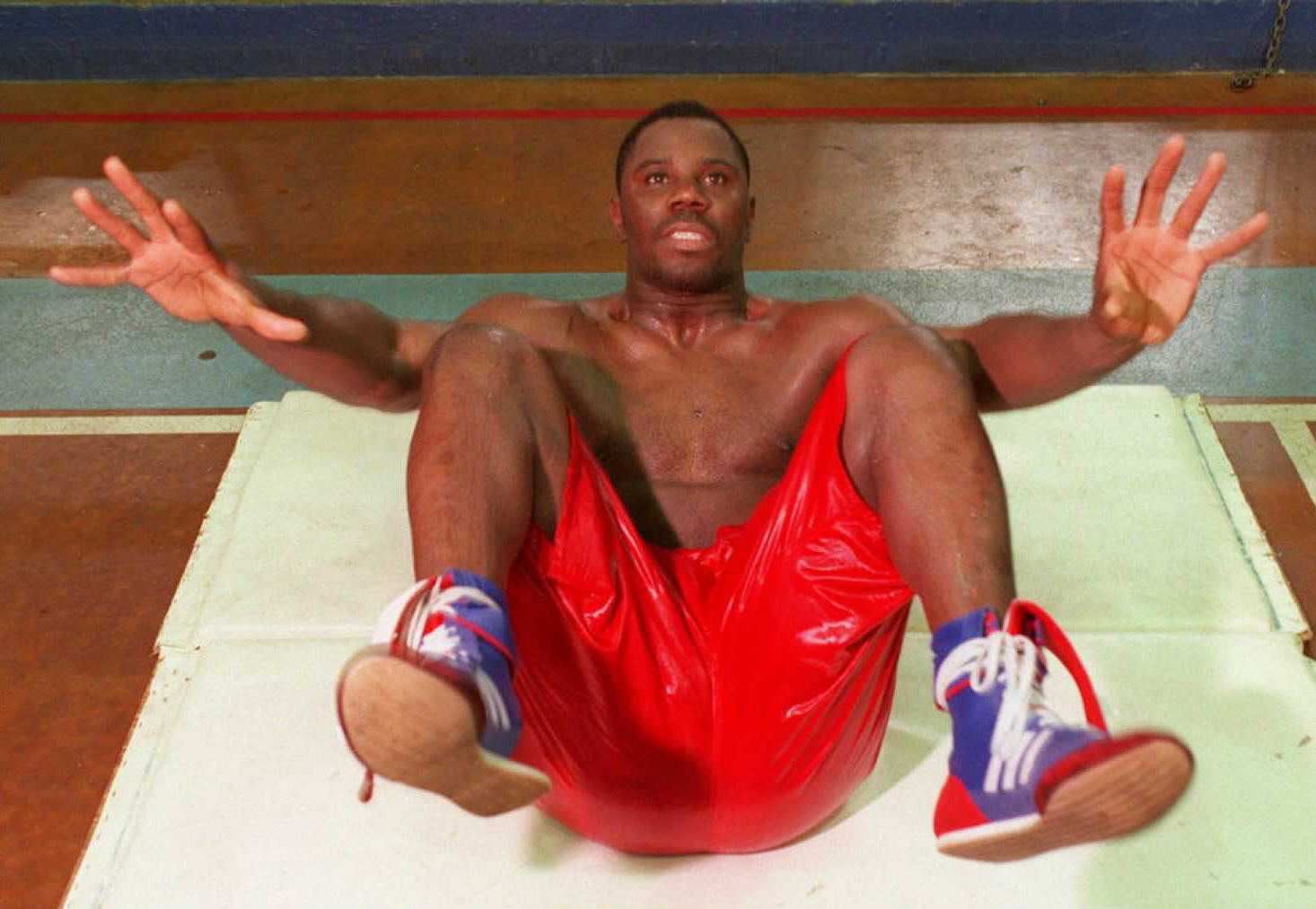

Nate Jones performs a Sit-Up during his training for the 1996 Olympic Games.

At 22 years old, boxing on the world’s biggest stage, he brought Cabrini-Green to a standstill. Rival gangs called a peace treaty for the day. Everyone’s focus was on Nate Jones and his chance for a gold medal in the heavyweight boxing division. Jones won his first two matches before losing to Canadian David Defiagbon in the semifinals, a performance that was good enough to secure a bronze medal and a place on the podium.

Jones’s career flamed out from there, as more legal troubles and a renewal of his battle with alcohol ultimately derailed his ability to maintain his boxing acumen. His last fight, in 2002, was a loss; and with the sport he’d been a part of all of his life now taken away from him, he experienced somewhat of a mid-life crisis. The streets of Chicago were once again beckoning, and the voices got louder by the day.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do with the rest of my life. I was frustrated,” Jones said. “I didn’t want to go back to the streets and start selling drugs.”

One day, his phone rang. It was Floyd Mayweather, and he’d just read an article about Jones’s retirement in a boxing magazine.

“Nate, you’d be a good trainer. You know boxing very well,” Mayweather said. “You can come work for me whenever you’re ready.”

Boxing was back in Jones’s life. A week later, he was in Las Vegas, Mayweather at his side.

RELATED: Can You Handle Floyd Mayweather Jr.’s ‘Money Walk’ Pull-Up?

Mayweather training with Nate Jones

The first time Jones met Floyd Mayweather, over a decade before that phone call, he had seen the characteristic that almost everyone notices about the braggadocios fighter.

“I didn’t like him because he talked too much,” Jones said.

It was 1994, and Jones and Mayweather were both in Milwaukee for the National Golden Gloves tournament, a win and move on, lose and go home-style bout. As the two fighters kept winning, they kept running into each other at successive weigh-ins.

“Every day at the weigh-in, Floyd would talk more sh*t than I’d ever heard in my life,” Jones said. “By the time the semifinals came, I walked up to him and said, “I can’t wait to see you fight, because you talk too much.”

On this particular day, Mayweather was fighting ahead of Jones, and he welcomed the attention. His fight lasted exactly one round.

“By the time he got out of the ring, he was the best fighter I’d ever seen,” Jones said.

Curious to watch the then-unranked Jones take on the number 3 heavyweight fighter in the nation, Mayweather stuck around for the fight. Jones knocked his man out in 15 seconds. The two stood in awe of each other, and like a scene out of Step Brothers, they instantly became best friends. They both won their respective weight classes at the Golden Gloves, and shortly after, Mayweather invited Jones to come live with him in Grand Rapids, Michigan, his hometown.

“He said, ‘You need to get away from Cabrini-Green and come up here with me.’ A week later I was in Grand Rapids,” Jones said.

To hear Jones tell it, the two spent almost every waking moment together. They trained together, boxed together and ran together. They also partied together—at least as much as one can party in Grand Rapids. They looked out for each other, with Jones, who was a heavyweight, often being mistaken for Mayweather’s bodyguard. Mayweather even visited Caprini-Green with Jones, meeting his mom and wife. The two were like college roommates who just so happened to be able to knock you out with one punch.

In 2006, ahead of Mayweather’s fight with Carlos Baldomeir, Floyd officially asked Jones to be in his corner for the first time. Jones was ecstatic, but petrified.

“It blew my mind. I couldn’t believe it,” Jones said. “I was nervous, but I knew I had to accept my challenge and do it.”

He’s been in Mayweather’s corner ever since, while also becoming a prominent trainer for other boxers, a door opened for him by the man he’s now known for almost 30 years. Jones believes boxing starts with the feet (“If your feet ain’t right, ain’t nothing right,” is a phrase he champions), something Mayweather has excelled at his whole career. And though Mayweather doesn’t need much ringside coaching at this point in his career, he and Jones have come up with their own code, which Jones uses to remind Mayweather to focus on minute things like throwing his punches straight or tendencies he’s seeing in the other fighter.

Along with Floyd Mayweather Sr. and Floyd’s uncle, Roger Mayweather, Jones is an integral part of Mayweather’s training crew, part of Mayweather’s larger “Money Team” conglomerate. Ahead of what might be the most hyped fight of Mayweather’s career, his long overdue bout with Manny Pacquiao, Jones has once again been by his side as Mayweather obsessively prepares. Admitting Mayweather’s love of words has rubbed off on him, Jones has a bold prediction for the biggest fight of the year.

“Pacquiao is so fundamentally unsound. There’s no comparison. I don’t know why people think this is going to be a good fight,” Jones said. “I just think Floyd will beat him, and it will be an easy fight. It won’t go more than 7 rounds.”

Maybe Mayweather’s nightmare turns in to a reality. Maybe Pacquiao beats him on May 2. Or maybe Mayweather pushes his record to 48-0, continues his chase of Rocky Marciano’s 49-0 record and goes down as the greatest boxer of all time. Whatever the result, Jones has already lived out two dreams, winning an Olympic medal and training one of the best fighters to ever live.

“Floyd opened the door for me as a trainer,” said Jones. “I love him for giving me an opportunity to find me a new way in life, because I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life after I retired.”

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

Mayweather’s Man: Trainer and Olympian Nate Jones and His Path From Jail to Boxing’s Biggest Stage

![]()

When you’re the trainer of the world’s most famous boxer, as Nate Jones is, you’ve got a few stories to tell. When you’ve made it out of one of the most infamous housing projects in America, as Nate Jones has, you’ve got a few more. And when your life has taken you from a jail cell to an Olympic podium and into the corner of arguably the greatest boxer of a generation, you could write a novel. But for now, you want to tell one specific story about when the boxer you train, Floyd Mayweather, woke up one morning in tears.

“Nate, what happened last night?” Jones recalls Mayweather asking in a panic.

Jones, unsure what Mayweather was talking about, asked him what he meant.

“Nate, I had a boxing match and I lost,” Mayweather said.

Jones pushed his wristwatch in front of Mayweather’s eyes. “Floyd, look at my watch,” he said. “That means you would have fought on Monday. The champ doesn’t fight on Monday, they fight on Saturday. You must have been dreaming.”

Mayweather just shook his head.

“It felt so real.”

Now Mayweather was gone, and Jones had no idea where he went. He yelled Floyd’s name throughout the house, with nary a response. Suddenly, the door opened, and a sweat-stained Mayweather emerged wearing a full tracksuit.

“Where have you been?” Jones asked.

“I went for a 10-mile run,” Mayweather said. “That dream felt too real.”

RELATED: Watch Floyd Mayweather’s Workout

Part of the Cabrini-Green housing projects in Chicago, which have since been torn down.

For the better part of his life, Nate Jones was the one chasing a dream, instead of helping another man chase his.

Jones grew up in Cabrini-Green, the notorious Chicago housing project, where his first experience throwing hands came in the streets. As a kid, he and his friends engaged in street fights, and Jones quickly became known as the guy who never lost.

“Anybody in my age bracket that would come to body blows with me in my projects, I would beat them,” Jones said.

They’d fight until someone got knocked down or started bleeding, or until one of them simply had enough and quit. Jones never quit.

Some of the older heads around the neighborhood took notice of Jones and the natural, albeit raw, way he threw punches. They placed him in boxing gloves and had him fight other kids that way. As he did with his bare knuckles, Jones kept on cleaning up.

“Everyone had heard about me,” Jones said. “No one wanted to fight me. They’d say, ‘There’s a young black kid that’s a good boxer. He can beat everybody.’”

None of it was technical, though. Jones had no formal boxing training, just a desire to avoid embarrassment in his tough neighborhood, where reputation was everything. Then, when he was 8 years old, Jones joined a boxing program that was starting up at Seward Park in Cabrini-Green, run by Tom O’Shea, a Chicago boxing legend. O’Shea was immediately drawn to Jones, whom he saw as a “natural” talent, and he began chipping away at the street fighting mentality that was drilled into Jones’s head.

That task would prove nearly impossible early on. Jones was terrible in the ring during his initial bouts, losing his first eight fights and threatening to quit in frustration. He would become enraged after losing, wanting to fight his opponent like he did on the streets of Chicago after the fight had already ended. O’Shea was his rock, encouraging him to stick with it as the losses piled up for the kid who had never lost a fight in his life.

Finally, something clicked. Jones remembers exactly when it happened. He was 11 years old, fighting in a national tournament. His opponent was a white kid sporting a Mohawk, and it scared Jones.

“The Mohawk scared me because I’d never seen anyone with a Mohawk before, except for Mr. T,” Jones said. “He intimidated me. But when I started fighting him and I started seeing how it was easy, that’s when I recognized that I can do this. He wasn’t as good as they were saying. That was the fight I recognized that I can really do this here. I beat that kid and really felt good.”

Jones didn’t lose again for a year and a half. He was launched on a career path that would culminate with a bronze medal in the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta—but not before he was convicted of auto theft and armed robbery. At the age if 18, he watched the 1992 Olympics from a jail cell at Western Illinois Correctional Institute. He also had a penchant for drinking, a liquid demon that floated in and out of his life like it flowed down his throat. But the ’96 Olympics was his goal, and he cleaned himself up enough to reach it.

Nate Jones performs a Sit-Up during his training for the 1996 Olympic Games.

At 22 years old, boxing on the world’s biggest stage, he brought Cabrini-Green to a standstill. Rival gangs called a peace treaty for the day. Everyone’s focus was on Nate Jones and his chance for a gold medal in the heavyweight boxing division. Jones won his first two matches before losing to Canadian David Defiagbon in the semifinals, a performance that was good enough to secure a bronze medal and a place on the podium.

Jones’s career flamed out from there, as more legal troubles and a renewal of his battle with alcohol ultimately derailed his ability to maintain his boxing acumen. His last fight, in 2002, was a loss; and with the sport he’d been a part of all of his life now taken away from him, he experienced somewhat of a mid-life crisis. The streets of Chicago were once again beckoning, and the voices got louder by the day.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do with the rest of my life. I was frustrated,” Jones said. “I didn’t want to go back to the streets and start selling drugs.”

One day, his phone rang. It was Floyd Mayweather, and he’d just read an article about Jones’s retirement in a boxing magazine.

“Nate, you’d be a good trainer. You know boxing very well,” Mayweather said. “You can come work for me whenever you’re ready.”

Boxing was back in Jones’s life. A week later, he was in Las Vegas, Mayweather at his side.

RELATED: Can You Handle Floyd Mayweather Jr.’s ‘Money Walk’ Pull-Up?

Mayweather training with Nate Jones

The first time Jones met Floyd Mayweather, over a decade before that phone call, he had seen the characteristic that almost everyone notices about the braggadocios fighter.

“I didn’t like him because he talked too much,” Jones said.

It was 1994, and Jones and Mayweather were both in Milwaukee for the National Golden Gloves tournament, a win and move on, lose and go home-style bout. As the two fighters kept winning, they kept running into each other at successive weigh-ins.

“Every day at the weigh-in, Floyd would talk more sh*t than I’d ever heard in my life,” Jones said. “By the time the semifinals came, I walked up to him and said, “I can’t wait to see you fight, because you talk too much.”

On this particular day, Mayweather was fighting ahead of Jones, and he welcomed the attention. His fight lasted exactly one round.

“By the time he got out of the ring, he was the best fighter I’d ever seen,” Jones said.

Curious to watch the then-unranked Jones take on the number 3 heavyweight fighter in the nation, Mayweather stuck around for the fight. Jones knocked his man out in 15 seconds. The two stood in awe of each other, and like a scene out of Step Brothers, they instantly became best friends. They both won their respective weight classes at the Golden Gloves, and shortly after, Mayweather invited Jones to come live with him in Grand Rapids, Michigan, his hometown.

“He said, ‘You need to get away from Cabrini-Green and come up here with me.’ A week later I was in Grand Rapids,” Jones said.

To hear Jones tell it, the two spent almost every waking moment together. They trained together, boxed together and ran together. They also partied together—at least as much as one can party in Grand Rapids. They looked out for each other, with Jones, who was a heavyweight, often being mistaken for Mayweather’s bodyguard. Mayweather even visited Caprini-Green with Jones, meeting his mom and wife. The two were like college roommates who just so happened to be able to knock you out with one punch.

In 2006, ahead of Mayweather’s fight with Carlos Baldomeir, Floyd officially asked Jones to be in his corner for the first time. Jones was ecstatic, but petrified.

“It blew my mind. I couldn’t believe it,” Jones said. “I was nervous, but I knew I had to accept my challenge and do it.”

He’s been in Mayweather’s corner ever since, while also becoming a prominent trainer for other boxers, a door opened for him by the man he’s now known for almost 30 years. Jones believes boxing starts with the feet (“If your feet ain’t right, ain’t nothing right,” is a phrase he champions), something Mayweather has excelled at his whole career. And though Mayweather doesn’t need much ringside coaching at this point in his career, he and Jones have come up with their own code, which Jones uses to remind Mayweather to focus on minute things like throwing his punches straight or tendencies he’s seeing in the other fighter.

Along with Floyd Mayweather Sr. and Floyd’s uncle, Roger Mayweather, Jones is an integral part of Mayweather’s training crew, part of Mayweather’s larger “Money Team” conglomerate. Ahead of what might be the most hyped fight of Mayweather’s career, his long overdue bout with Manny Pacquiao, Jones has once again been by his side as Mayweather obsessively prepares. Admitting Mayweather’s love of words has rubbed off on him, Jones has a bold prediction for the biggest fight of the year.

“Pacquiao is so fundamentally unsound. There’s no comparison. I don’t know why people think this is going to be a good fight,” Jones said. “I just think Floyd will beat him, and it will be an easy fight. It won’t go more than 7 rounds.”

Maybe Mayweather’s nightmare turns in to a reality. Maybe Pacquiao beats him on May 2. Or maybe Mayweather pushes his record to 48-0, continues his chase of Rocky Marciano’s 49-0 record and goes down as the greatest boxer of all time. Whatever the result, Jones has already lived out two dreams, winning an Olympic medal and training one of the best fighters to ever live.

“Floyd opened the door for me as a trainer,” said Jones. “I love him for giving me an opportunity to find me a new way in life, because I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life after I retired.”