‘Core Stability’ Is a Trendy Training Buzzword. Here’s Why It’s Often Misused

You’ve probably heard a trainer or coach preach the importance of having a “stable core.” Terms like “core training” or “core stability training” have become increasingly trendy buzzwords, and now a huge number of exercises and movements are being classified under their umbrella, for better or worse.

But what exactly is core stability? To answer that question, we must define what muscles are included in the “core.” The not-so-simple answer to this is that “we aren’t sure.” Scientists can’t agree on a universal definition for the term, and everyone seems to have a different answer to the question. So instead of orienting our definition of the “core” in anatomical terms, let’s define it a different way.

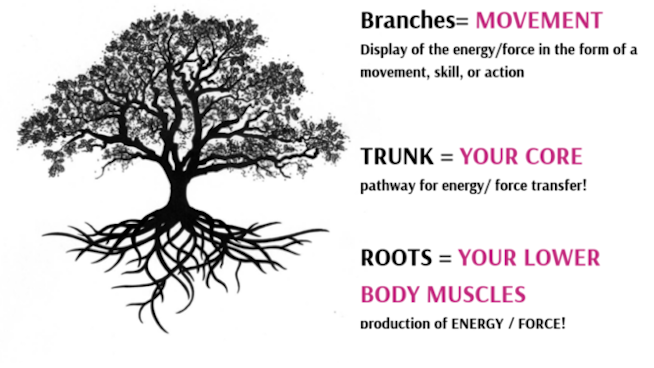

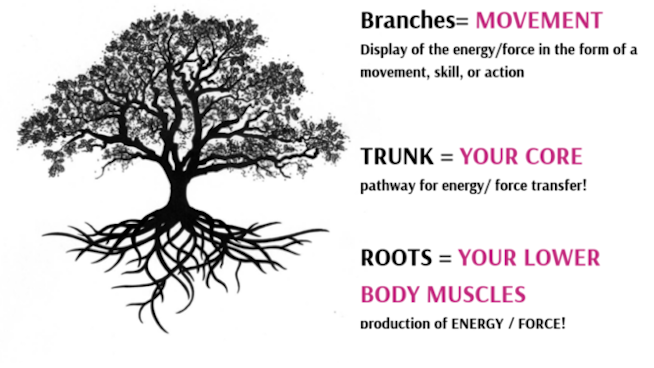

Picture our bodies like a tree. There isn’t necessarily a true “core” of a tree, but trees have trunks that serve as the connection pathway between the roots, branches and leaves. I like to think this is very similar to how our bodies function in sport and movement.

Athletes need engage in high-intensity actions that require the appropriate machinery and mechanisms to carry out these sporting movements. High-intensity actions include:

- Sprinting

- Jumping

- Change of direction

Let’s think about a volleyball player spiking a ball. To do this efficiently, she must:

- Produce force through the ground to jump by loading her lower-body musculature (the roots)

- Transmit the force to her upper body (through the ‘trunk’)

- Execute the transfer of force by hitting the volleyball (branches/leaves)

The presence of a weak link in this chain may lead to energy leaks and less powerful sporting movements. The bottomline is that a strong “connection pathway” is critical to reducing these energy leaks.

The demands of sport are quite different from each other (think gymnastics versus basketball) so it’s difficult to decipher what exactly defines trunk stability; plus, the demands of the trunk will be different for each sport. However, We know that to transmit forces through the body, it’s advantageous to have an efficient pathway.

For example: A basketball player going for a layup. To execute this movement most effectively, they will need to stabilize themselves on a single leg and propel their body upward. To be as stable as possible, they will have to minimize horizontal movements, as that’s wasted energy which could be channeled to accelerating upwards.

So how do we train core stability? The simple answer is via strength training. There’s a lot of confusion around this topic, however, so let’s also hit on some methods that have been found to be largely ineffective:

- Long-duration or high-rep “core” exercises that utilize little resistance (ex: a two-minute-long plank)

- Crunches

- Unstable surface training (such as Squats on a BOSU Ball)

So clearly, a lot of what’s being labeled “core training” is at best a lowly effective method of building trunk stability.

What has been shown is that traditional strength training (such as Squats and Olympic lifts) can help develop the machinery (neural adaptations and strength) to efficiently carry out high-intensity actions.

As a result, this may:

- 1. Reduce injury

- 2. Increase power production

- 3. Increase strength to help produce more force (jump higher, run faster, etc.)

The problem with many people’s approach to core stability and core training is they design isolated exercises meant to train these qualities, when in reality, they have little to no transfer to sport performance. On the other hand, strength training is an imperative part of the performance enhancement process; it helps prepare the athlete to handle large amounts of stress and functions as a tool to execute proper movement patterns as they pertain to sport.

In summation, lifting moderate-to-heavy loads via traditional strength training methods is going to do the most for your core/trunk stability. While the gimmicky unstable surface training that’s often being labeled as “core” training on Instagram might look cool, the reality is that it’s far from an efficient use of time for healthy athletes looking to enhance their performance.

References:

1. Gonzalo-Skok, O., Tous-Fajardo, J., Suarez-Arrones, L., Arjol-Serrano, J. L., Casajús, J. A., & Mendez-Villanueva, A. (2017). Single-Leg Power Output and Between-Limbs Imbalances in Team-Sport Players: Unilateral Versus Bilateral Combined Resistance Training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 12(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0743

2. Hibbs, A. E., Thompson, K. G., French, D., Wrigley, A., & Spears, I. (2008). “Optimizing Performance by Improving Core Stability and Core Strength,” Sports Medicine, 38(12), 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838120-00004

3. Leetun, D. T., Ireland, M. L., Willson, J. D., Ballantyne, B. M., & Davis, I. (2004). “Core Stability Measures as Risk Factors for Lower Extremity Injury in Athletes,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(6), 926-934.

4. McGill, S. (2010). “Core Training: Evidence Translating to Better Performance and Injury Prevention,” Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(3), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181df4521

5. Wirth, K., Hartmann, H., Mickel, C., Szilvas, E., Keiner, M., & Sander, A. (2017). “Core Stability in Athletes: A Critical Analysis of Current Guidelines,” Sports Medicine; Auckland, 47(3), 401–414. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0597-7

6. Young, W. B. (2006). “Transfer of Strength and Power Training to Sports Performance,” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 1(2), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.1.2.74

READ MORE:

- 5 Core Exercises Young Athletes Should Be Using Instead of Sit-Ups

- Why ‘Anti’ Movements Are an Athlete’s Key to Functional Core Strength

- Why Your Ab Workout Isn’t Actually Strengthening Your Core

Photo Credit: FlamingoImages/iStock

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

‘Core Stability’ Is a Trendy Training Buzzword. Here’s Why It’s Often Misused

You’ve probably heard a trainer or coach preach the importance of having a “stable core.” Terms like “core training” or “core stability training” have become increasingly trendy buzzwords, and now a huge number of exercises and movements are being classified under their umbrella, for better or worse.

But what exactly is core stability? To answer that question, we must define what muscles are included in the “core.” The not-so-simple answer to this is that “we aren’t sure.” Scientists can’t agree on a universal definition for the term, and everyone seems to have a different answer to the question. So instead of orienting our definition of the “core” in anatomical terms, let’s define it a different way.

Picture our bodies like a tree. There isn’t necessarily a true “core” of a tree, but trees have trunks that serve as the connection pathway between the roots, branches and leaves. I like to think this is very similar to how our bodies function in sport and movement.

Athletes need engage in high-intensity actions that require the appropriate machinery and mechanisms to carry out these sporting movements. High-intensity actions include:

- Sprinting

- Jumping

- Change of direction

Let’s think about a volleyball player spiking a ball. To do this efficiently, she must:

- Produce force through the ground to jump by loading her lower-body musculature (the roots)

- Transmit the force to her upper body (through the ‘trunk’)

- Execute the transfer of force by hitting the volleyball (branches/leaves)

The presence of a weak link in this chain may lead to energy leaks and less powerful sporting movements. The bottomline is that a strong “connection pathway” is critical to reducing these energy leaks.

The demands of sport are quite different from each other (think gymnastics versus basketball) so it’s difficult to decipher what exactly defines trunk stability; plus, the demands of the trunk will be different for each sport. However, We know that to transmit forces through the body, it’s advantageous to have an efficient pathway.

For example: A basketball player going for a layup. To execute this movement most effectively, they will need to stabilize themselves on a single leg and propel their body upward. To be as stable as possible, they will have to minimize horizontal movements, as that’s wasted energy which could be channeled to accelerating upwards.

So how do we train core stability? The simple answer is via strength training. There’s a lot of confusion around this topic, however, so let’s also hit on some methods that have been found to be largely ineffective:

- Long-duration or high-rep “core” exercises that utilize little resistance (ex: a two-minute-long plank)

- Crunches

- Unstable surface training (such as Squats on a BOSU Ball)

So clearly, a lot of what’s being labeled “core training” is at best a lowly effective method of building trunk stability.

What has been shown is that traditional strength training (such as Squats and Olympic lifts) can help develop the machinery (neural adaptations and strength) to efficiently carry out high-intensity actions.

As a result, this may:

- 1. Reduce injury

- 2. Increase power production

- 3. Increase strength to help produce more force (jump higher, run faster, etc.)

The problem with many people’s approach to core stability and core training is they design isolated exercises meant to train these qualities, when in reality, they have little to no transfer to sport performance. On the other hand, strength training is an imperative part of the performance enhancement process; it helps prepare the athlete to handle large amounts of stress and functions as a tool to execute proper movement patterns as they pertain to sport.

In summation, lifting moderate-to-heavy loads via traditional strength training methods is going to do the most for your core/trunk stability. While the gimmicky unstable surface training that’s often being labeled as “core” training on Instagram might look cool, the reality is that it’s far from an efficient use of time for healthy athletes looking to enhance their performance.

References:

1. Gonzalo-Skok, O., Tous-Fajardo, J., Suarez-Arrones, L., Arjol-Serrano, J. L., Casajús, J. A., & Mendez-Villanueva, A. (2017). Single-Leg Power Output and Between-Limbs Imbalances in Team-Sport Players: Unilateral Versus Bilateral Combined Resistance Training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 12(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0743

2. Hibbs, A. E., Thompson, K. G., French, D., Wrigley, A., & Spears, I. (2008). “Optimizing Performance by Improving Core Stability and Core Strength,” Sports Medicine, 38(12), 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838120-00004

3. Leetun, D. T., Ireland, M. L., Willson, J. D., Ballantyne, B. M., & Davis, I. (2004). “Core Stability Measures as Risk Factors for Lower Extremity Injury in Athletes,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(6), 926-934.

4. McGill, S. (2010). “Core Training: Evidence Translating to Better Performance and Injury Prevention,” Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(3), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181df4521

5. Wirth, K., Hartmann, H., Mickel, C., Szilvas, E., Keiner, M., & Sander, A. (2017). “Core Stability in Athletes: A Critical Analysis of Current Guidelines,” Sports Medicine; Auckland, 47(3), 401–414. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0597-7

6. Young, W. B. (2006). “Transfer of Strength and Power Training to Sports Performance,” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 1(2), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.1.2.74

READ MORE:

- 5 Core Exercises Young Athletes Should Be Using Instead of Sit-Ups

- Why ‘Anti’ Movements Are an Athlete’s Key to Functional Core Strength

- Why Your Ab Workout Isn’t Actually Strengthening Your Core

Photo Credit: FlamingoImages/iStock