A Simple Strategy for Rehabbing a Shoulder Injury

The shoulder girdle is an intricate joint that carries a great deal of responsibility in our daily function. This responsibility is enhanced for athletes due to the increased amount of high-level activity required by the upper extremity during training and competition. If shoulder health is not addressed with a prevention program before an injury, or especially with a rehab program after an injury, the overall function will be sub-optimal.

This article will provide information on basic shoulder anatomy, common shoulder injuries and general shoulder rehab that will allow athletes to combat various shoulder injuries including but not limited to rotator cuff tendinitis, shoulder instability and shoulder impingement.

The rotator cuff is a group of four scapulohumeral muscles that aid in the movement of the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) throughout much of its range of motion. They are considered scapulohumeral muscles because of their origin on the scapula or “shoulder blade” and insertion on the humerus. The shoulder girdle is a ball-and-socket joint just like the hip, so it has three degrees of freedom, which makes it highly movable.

So, what does this mean? The shoulder relies heavily on dynamic stabilization from muscles and tendons, which is offered primarily by the scapulohumeral muscles. The rotator cuff group offers vital stabilization and movement of the upper extremity. As stated before, this group includes four muscles, all of which offer specific actions at the shoulder.

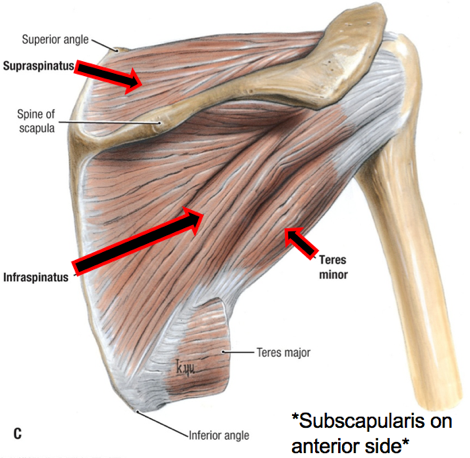

The four rotator cuff muscles or “SITS” muscles include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis, all of which form a “cuff” which helps to form the joint capsule of the shoulder.

The supraspinatus is the most superior of the rotator cuff, sitting atop the scapula. This is the only rotator cuff muscle that does not directly help with rotation. Its main action is to initiate arm abduction (moving the arm away from the body) by assisting the deltoid.

The infraspinatus sits below the supraspinatus and spine of the scapula. Its individual action along with the teres minor is external rotation of the arm. This is commonly the muscle aggravated or injured during low bar Back Squats, pitching or overhead activities.

The teres minor sits below the infraspinatus on the scapula. This individual muscle again works with the infraspinatus to externally rotate the arm. It also is responsible for arm adduction (bringing the arm toward the body.) The majority of the muscle belly and tendon is covered by the deltoid muscle group.

The subscapularis arises from a different area of the scapula. It sits in the subscapular fossa on the anterior, or front, of the scapula. Its main responsibility is internal rotation of the arm, while also assisting the teres minor in arm adduction.

There are many things that come into play with rotator cuff injuries or shoulder injuries in general. The first of which is the specific mechanism or reason for onset. It may not always be clear whether it is acute or chronic, but know that can make identifying the problem much easier.

At the shoulder girdle, it is often difficult to determine injuries due to the intricacy of the joint itself. So many structures run through the joint—tendons, bursae, bony structures, etc., that if one injury or irritation occurs, it can lead to the onset of other injuries. Let’s start with a simple rotator cuff strain.

Rotator cuff strains are increasingly common in sport, due to many overhead activities, reliance on arm movement and the responsibility we put on the shoulder to perform many actions throughout activities of daily living. Strains occur when tissue attempts to withstand a load it cannot, and from there muscle fibers begin to stretch. Strains can be graded on a 1, 2 or 3 scale, depending on the severity of the fibers stretched or torn. For reference, we commonly hear a grade three strain referred to as a “tear,” so again it all depends on the severity of the damage.

Another common rotator cuff tendon injury is tendinitis, which occurs from repetitive micro traumas or overuse of muscle fibers. Any term that ends in the suffix -itis, refers to inflammation. So, tendinitis is inflammation of tendons from the chronic overuse or micro traumas. If not treated correctly this can lead to long-term, more chronic issues such as tendinopathies, which are generalized as diseases or deterioration of tissue and can lead to constant, long-term pain. This deterioration is caused from acute injuries not being tended to correctly, which is followed by an exacerbation of pain from poor blood flow to each tendon and in turn, lack of healing.

Another common pathology of the rotator cuff is impingement, which occurs when the space that the rotator cuff tendons run through becomes decreased. This space, called the coracoacromial space, is occupied by the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, in addition to other structures including, but not limited to the subacromial bursa and long head of the biceps. When this space becomes enclosed, structures begin to rub on each other during movement, and this can cause the rotator cuff tendons to become inflamed. This inflammation causes a further closing of the subacromial space and increased pressure on the tendons.

When we look at the long-term complications from any of these injuries we see increased instability, decreased range-of-motion (ROM), labral injuries and increased risk of additional tissue damage. This decreased ROM, specifically with internal rotation can lead to increased stiffness of the posterior capsule. This can cause further issues including weakness of the dynamic stabilizers of the GH joint, poor biomechanics of the shoulder and improper rhythm of the scapula. This can cause overhead movements, throwing activities and general daily tasks to become increasingly painful and bothersome.

So before we get into the rehabilitation plan, let’s walk through a few things you can do when you begin to have shoulder pain.

What To Do When You Have Pain?

Take a minute and think about what the pain is like, how severe it is, during what movements it aches and how long has the pain been occurring? These are very helpful in determining what the specific injury may be. However, knowledge of a previous injury to the shoulder and mechanism of injury are extremely important as well.

Next, note all of the other symptoms, such as clicking, popping, redness, inflammation, numbness, tingling, weakness, diminished pulse, etc. The more information you have, the better idea you will have of what your next step should be. My goal is to give you tools that can keep you out of the doctor’s office or clinic and be proactive with your injuries.

Now What?

The routines will be slightly different depending on when they are used, but regardless, the highlighted plan at the end of this article can act as a great injury prevention warm-up or rehabilitation technique.

General Shoulder Rehab

The goal of the shoulder rehab programming is to restore and improve your shoulder mobility. Many times, we do not have the proper shoulder mobility and ROM before we add weight and resistance. Then we start to develop poor movement patterns because our muscles are trying to shorten and lengthen in positions where they are not as efficient. This can cause pathological movement patterns, muscle imbalances and injury. So, I encourage you to look at and employ the mobility and stretching techniques below. From there, once you feel comfortable, add the strengthening movements. If you have any feedback, comments or questions about specific injury rehabilitation plans please contact me and always remember to #HealByMoving.

Passive Flexibility/Mobility (See video @toddsportsmed)

All completed for 30 seconds, preferably both arms.

- External Rotation

- Internal Rotation

- Horizontal adduction

- Shoulder abduction

Strengthening/Stability

- Use as a prehab/warm up circuit: 1 round each exercise (both arms) for 10 repetitions.

- Use as a rehabilitation program: 2 rounds each exercise (both arms) for 15 repetitions.

a. External rotation (Shoulder in neutral, elbow at 90 degrees)

b. External rotation (Shoulder at 90 degrees, elbow at 90 degrees)

c. Internal rotation (Shoulder at 90 degrees, elbow at 90 degrees)

d. Internal rotation (Shoulder in neutral, elbow at 90 degrees)

e. Horizontal adduction

f. Band Face Pulls

g. Band Pullovers

h. Band Pull-A-Parts

i. Prone Scaption

READ MORE:

- Shoulder Injury Prevention Exercises for Athletes

- Build Stable Shoulders and a Strong Core With Single-Arm Planks

- The Perfect Shoulder Workout for Strength and Durability

- The Strange Shoulder Injury That is Sidelining MLB Pitchers

ChesiireCat/iStockPhoto

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

A Simple Strategy for Rehabbing a Shoulder Injury

The shoulder girdle is an intricate joint that carries a great deal of responsibility in our daily function. This responsibility is enhanced for athletes due to the increased amount of high-level activity required by the upper extremity during training and competition. If shoulder health is not addressed with a prevention program before an injury, or especially with a rehab program after an injury, the overall function will be sub-optimal.

This article will provide information on basic shoulder anatomy, common shoulder injuries and general shoulder rehab that will allow athletes to combat various shoulder injuries including but not limited to rotator cuff tendinitis, shoulder instability and shoulder impingement.

The rotator cuff is a group of four scapulohumeral muscles that aid in the movement of the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) throughout much of its range of motion. They are considered scapulohumeral muscles because of their origin on the scapula or “shoulder blade” and insertion on the humerus. The shoulder girdle is a ball-and-socket joint just like the hip, so it has three degrees of freedom, which makes it highly movable.

So, what does this mean? The shoulder relies heavily on dynamic stabilization from muscles and tendons, which is offered primarily by the scapulohumeral muscles. The rotator cuff group offers vital stabilization and movement of the upper extremity. As stated before, this group includes four muscles, all of which offer specific actions at the shoulder.

The four rotator cuff muscles or “SITS” muscles include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis, all of which form a “cuff” which helps to form the joint capsule of the shoulder.

The supraspinatus is the most superior of the rotator cuff, sitting atop the scapula. This is the only rotator cuff muscle that does not directly help with rotation. Its main action is to initiate arm abduction (moving the arm away from the body) by assisting the deltoid.

The infraspinatus sits below the supraspinatus and spine of the scapula. Its individual action along with the teres minor is external rotation of the arm. This is commonly the muscle aggravated or injured during low bar Back Squats, pitching or overhead activities.

The teres minor sits below the infraspinatus on the scapula. This individual muscle again works with the infraspinatus to externally rotate the arm. It also is responsible for arm adduction (bringing the arm toward the body.) The majority of the muscle belly and tendon is covered by the deltoid muscle group.

The subscapularis arises from a different area of the scapula. It sits in the subscapular fossa on the anterior, or front, of the scapula. Its main responsibility is internal rotation of the arm, while also assisting the teres minor in arm adduction.

There are many things that come into play with rotator cuff injuries or shoulder injuries in general. The first of which is the specific mechanism or reason for onset. It may not always be clear whether it is acute or chronic, but know that can make identifying the problem much easier.

At the shoulder girdle, it is often difficult to determine injuries due to the intricacy of the joint itself. So many structures run through the joint—tendons, bursae, bony structures, etc., that if one injury or irritation occurs, it can lead to the onset of other injuries. Let’s start with a simple rotator cuff strain.

Rotator cuff strains are increasingly common in sport, due to many overhead activities, reliance on arm movement and the responsibility we put on the shoulder to perform many actions throughout activities of daily living. Strains occur when tissue attempts to withstand a load it cannot, and from there muscle fibers begin to stretch. Strains can be graded on a 1, 2 or 3 scale, depending on the severity of the fibers stretched or torn. For reference, we commonly hear a grade three strain referred to as a “tear,” so again it all depends on the severity of the damage.

Another common rotator cuff tendon injury is tendinitis, which occurs from repetitive micro traumas or overuse of muscle fibers. Any term that ends in the suffix -itis, refers to inflammation. So, tendinitis is inflammation of tendons from the chronic overuse or micro traumas. If not treated correctly this can lead to long-term, more chronic issues such as tendinopathies, which are generalized as diseases or deterioration of tissue and can lead to constant, long-term pain. This deterioration is caused from acute injuries not being tended to correctly, which is followed by an exacerbation of pain from poor blood flow to each tendon and in turn, lack of healing.

Another common pathology of the rotator cuff is impingement, which occurs when the space that the rotator cuff tendons run through becomes decreased. This space, called the coracoacromial space, is occupied by the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, in addition to other structures including, but not limited to the subacromial bursa and long head of the biceps. When this space becomes enclosed, structures begin to rub on each other during movement, and this can cause the rotator cuff tendons to become inflamed. This inflammation causes a further closing of the subacromial space and increased pressure on the tendons.

When we look at the long-term complications from any of these injuries we see increased instability, decreased range-of-motion (ROM), labral injuries and increased risk of additional tissue damage. This decreased ROM, specifically with internal rotation can lead to increased stiffness of the posterior capsule. This can cause further issues including weakness of the dynamic stabilizers of the GH joint, poor biomechanics of the shoulder and improper rhythm of the scapula. This can cause overhead movements, throwing activities and general daily tasks to become increasingly painful and bothersome.

So before we get into the rehabilitation plan, let’s walk through a few things you can do when you begin to have shoulder pain.

What To Do When You Have Pain?

Take a minute and think about what the pain is like, how severe it is, during what movements it aches and how long has the pain been occurring? These are very helpful in determining what the specific injury may be. However, knowledge of a previous injury to the shoulder and mechanism of injury are extremely important as well.

Next, note all of the other symptoms, such as clicking, popping, redness, inflammation, numbness, tingling, weakness, diminished pulse, etc. The more information you have, the better idea you will have of what your next step should be. My goal is to give you tools that can keep you out of the doctor’s office or clinic and be proactive with your injuries.

Now What?

The routines will be slightly different depending on when they are used, but regardless, the highlighted plan at the end of this article can act as a great injury prevention warm-up or rehabilitation technique.

General Shoulder Rehab

The goal of the shoulder rehab programming is to restore and improve your shoulder mobility. Many times, we do not have the proper shoulder mobility and ROM before we add weight and resistance. Then we start to develop poor movement patterns because our muscles are trying to shorten and lengthen in positions where they are not as efficient. This can cause pathological movement patterns, muscle imbalances and injury. So, I encourage you to look at and employ the mobility and stretching techniques below. From there, once you feel comfortable, add the strengthening movements. If you have any feedback, comments or questions about specific injury rehabilitation plans please contact me and always remember to #HealByMoving.

Passive Flexibility/Mobility (See video @toddsportsmed)

All completed for 30 seconds, preferably both arms.

- External Rotation

- Internal Rotation

- Horizontal adduction

- Shoulder abduction

Strengthening/Stability

- Use as a prehab/warm up circuit: 1 round each exercise (both arms) for 10 repetitions.

- Use as a rehabilitation program: 2 rounds each exercise (both arms) for 15 repetitions.

a. External rotation (Shoulder in neutral, elbow at 90 degrees)

b. External rotation (Shoulder at 90 degrees, elbow at 90 degrees)

c. Internal rotation (Shoulder at 90 degrees, elbow at 90 degrees)

d. Internal rotation (Shoulder in neutral, elbow at 90 degrees)

e. Horizontal adduction

f. Band Face Pulls

g. Band Pullovers

h. Band Pull-A-Parts

i. Prone Scaption

READ MORE:

- Shoulder Injury Prevention Exercises for Athletes

- Build Stable Shoulders and a Strong Core With Single-Arm Planks

- The Perfect Shoulder Workout for Strength and Durability

- The Strange Shoulder Injury That is Sidelining MLB Pitchers

ChesiireCat/iStockPhoto