Why Training Hard Every Day Is a Terrible Idea

Athletes are under constant pressure to improve and accelerate their performance. A young athlete looking to make it into D1 sports can often feel like they have to do more all the time. More is better, right?

That concept has long been glorified when it comes to training.

People like to say things like “No Days Off” or “Your Workout is My Warm-Up.”

They believe that if they do more than the other guy, then they’ll improve at a faster rate. Although that’s true in some sense, particularly if the other guy is doing very little, there’s absolutely a point of diminishing returns. Just as the idea that you have to sleep less to be successful has been thoroughly debunked, we need to push back against this idea that killing yourself every day in the gym is something to strive for.

Instead of “No Days Off,” I prefer the line “Train Hard, but Train Smart.” Admittedly, it’s not quite as catchy, but proper training is based in science, not snappy hashtags.

The human body is a complex system which requires strain to create positive adaptations.

Without a stimulus, the body has no incentive to change. If it doesn’t feel like it has to, it won’t. It will save the energy needed to create adaptations like building lean muscle mass and instead use it on other things. This is the innate nature of our body. The type of adaptations athletes are usually after does indeed require significant amounts of strenuous training, but it’s a balancing act.

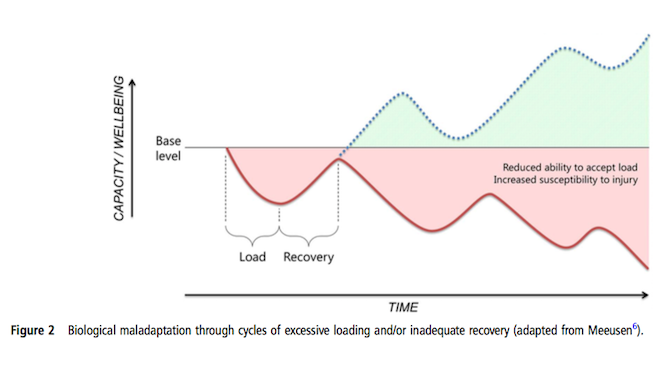

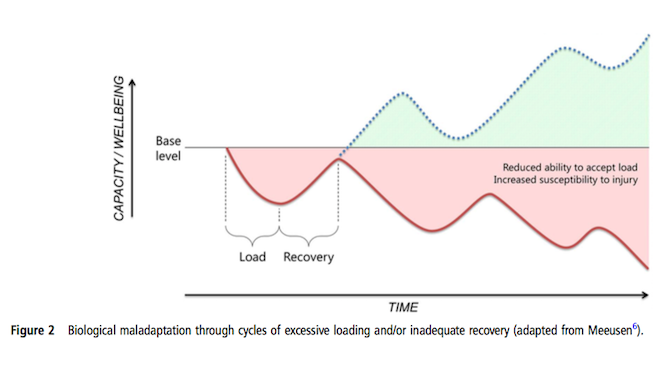

Strain can be visualized as peaks in a graph. An effective picture would show peaks and dips representing intense days of training followed by rest or low-intensity days. These days allow for recovery from the last intense session and adaptation can take place. Any well-designed program will have these small peaks and dips, but the overall direction of that trend would be upwards, as adequate rest is allowing adaptation to take place and progressive overload to occur. You can see this in the green portion of this chart:

Photo via the text Recovery For Performance in Sport from Human Kinetics

If your training lacks intensity, you don’t really need to worry too much about recovery, but you also won’t be making much progress due to the fact you’re lacking a stimulus for your body to significantly change.

On the flip side, if your training is always intense yet you consistently neglect recovery and never mix in more low-intensity or rest days, your long-term performance ends up suffering. You can see what that looks like in the red portion of the above chart.

But how much work is too much? And how much recovery is enough? It’s a tricky question. Everyone is different and every athlete has different goals. Genetics also play a large part in the equation.

The nervous system plays one of the most important roles when it comes to your recovery and performance. Think of your nervous system as a wind-up flashlight. When it’s fully wound up, it produces a brilliant light that illuminates the room. But when it’s in need of re-winding, that light is flickering and dull. After a couple recovery days, you will have “wound up” your flashlight and be able to train at a maximum intensity. Then, after 1-2 days of max training, your nervous system will likely be shot and in need of recovery to “re-wind.” You can’t do max training all day every day. Otherwise, you’ll burn out.

This doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly suffer some catastrophic injury, though you do increase your risk of such incidents. In the sense, “burning out” means you’re overtraining.

In the text Essentials of Strength and Conditioning, a common cause of overtraining is cited as “a rate of progressive overload that is too high. That is, increasing either the volume or intensity (or both) too rapidly over a period of several weeks or months with insufficient recovery can result in greater structural damage and, potentially, overtraining (OTS)…A mistake in the prescription of any acute program variable could theoretically contribute to OTS if it is consistently repeated over time. This can often occur when highly motivated athletes use a high volume of heavy training loads with high training frequency and take limited rest to recover between workouts.”

The red portion in the above chart is what overtraining can look like. When you consistently disrespect the balance between strain and recovery for a prolonged period of time, the body will no longer be able to adapt to the stress of training. No adaptations, no improvement. Suddenly, that “No Days Off” mindset has put you in a position where you have no choice but to rest and recover. If you’re lucky, you’ll realize this before you suffer a significant injury, but it still may take weeks or months to fully recover from overtraining.

The initial warning signs that you’re on the road to overtraining include decreased performance and increased fatigue.

Over time, more abnormal symptoms can appear, including waking up in the middle of night, being unable to fall asleep at night, a significantly raised resting heart rate, recurring headaches, reduced appetite, irritability, and/or a lack of competitive drive.

If you find yourself in this position, be open to taking a week or two off to wind that torch back up. Otherwise, you are only burying yourself deeper! A week “off” doesn’t necessarily mean lying in bed all day. It just means significantly decreasing the intensity of your training and allowing your body an honest opportunity to recover. If you think you are overtraining, you should also talk to your coach, athletic trainer and/or doctor about the topic.

How can we avoid overtraining in the first place?

One easy way is to record and monitor your fatigue levels during workouts using Rate of Perceived Exertion, or RPE.

Using a scale of 1-10, 10 being the hardest session you’ve ever done and 1 being a super easy, barely-break-a-sweat workout, you assign a score to each training session shortly after you’ve completed it (ideally immediately after you’ve completed it).

As a general rule of thumb, if you rate a session as an 8 or higher, hold back for a day or two before hitting another hard session. Ultimately, if you were to plot your RPEs on a chart, there should be consistent ups and downs over time.

Another more scientific way of recording and monitoring your fatigue is through Heart Rate Variability (HRV). HRV can be a great tool for understanding where your resting heart rate stands each morning. This is done by a device (Heart Rate Monitor) measuring your heart rate, and an App on your phone recording the variability within the beats. The more rhythmic your heartbeat, the better recovered you are. It’s actually really simple, and HRV devices are quite affordable.

As an athlete, your goal is continuous, sustainable improvement. Be honest when you feel you may be veering into overtraining. If you do your own program, allow yourself a couple days off and see if your symptoms improve. If you follow a program from a coach, be up front about your symptoms and discuss scaling things back for a bit. If they’re worth their salt, they’ll be grateful for your honesty and willing to find a solution.

Photo Credit: martin-dm/iStock, BMJ

References:

Budgett, R. (1998). “Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndrome.” British Journal Of Sports Medicine, 32(2), 107-110.

Koutedakis Y, Budgett R, Faulmann L. “Rest in underperforming elite competitors.” Br J Sports Med 1990;24:248– 52.

Soligard, T., Schwellnus, M., Alonso, J., Bahr, R., Clarsen, B., & Dijkstra, H. et al. (2016). “How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury.” British Journal Of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1030-1041.

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

Why Training Hard Every Day Is a Terrible Idea

Athletes are under constant pressure to improve and accelerate their performance. A young athlete looking to make it into D1 sports can often feel like they have to do more all the time. More is better, right?

That concept has long been glorified when it comes to training.

People like to say things like “No Days Off” or “Your Workout is My Warm-Up.”

They believe that if they do more than the other guy, then they’ll improve at a faster rate. Although that’s true in some sense, particularly if the other guy is doing very little, there’s absolutely a point of diminishing returns. Just as the idea that you have to sleep less to be successful has been thoroughly debunked, we need to push back against this idea that killing yourself every day in the gym is something to strive for.

Instead of “No Days Off,” I prefer the line “Train Hard, but Train Smart.” Admittedly, it’s not quite as catchy, but proper training is based in science, not snappy hashtags.

The human body is a complex system which requires strain to create positive adaptations.

Without a stimulus, the body has no incentive to change. If it doesn’t feel like it has to, it won’t. It will save the energy needed to create adaptations like building lean muscle mass and instead use it on other things. This is the innate nature of our body. The type of adaptations athletes are usually after does indeed require significant amounts of strenuous training, but it’s a balancing act.

Strain can be visualized as peaks in a graph. An effective picture would show peaks and dips representing intense days of training followed by rest or low-intensity days. These days allow for recovery from the last intense session and adaptation can take place. Any well-designed program will have these small peaks and dips, but the overall direction of that trend would be upwards, as adequate rest is allowing adaptation to take place and progressive overload to occur. You can see this in the green portion of this chart:

Photo via the text Recovery For Performance in Sport from Human Kinetics

If your training lacks intensity, you don’t really need to worry too much about recovery, but you also won’t be making much progress due to the fact you’re lacking a stimulus for your body to significantly change.

On the flip side, if your training is always intense yet you consistently neglect recovery and never mix in more low-intensity or rest days, your long-term performance ends up suffering. You can see what that looks like in the red portion of the above chart.

But how much work is too much? And how much recovery is enough? It’s a tricky question. Everyone is different and every athlete has different goals. Genetics also play a large part in the equation.

The nervous system plays one of the most important roles when it comes to your recovery and performance. Think of your nervous system as a wind-up flashlight. When it’s fully wound up, it produces a brilliant light that illuminates the room. But when it’s in need of re-winding, that light is flickering and dull. After a couple recovery days, you will have “wound up” your flashlight and be able to train at a maximum intensity. Then, after 1-2 days of max training, your nervous system will likely be shot and in need of recovery to “re-wind.” You can’t do max training all day every day. Otherwise, you’ll burn out.

This doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly suffer some catastrophic injury, though you do increase your risk of such incidents. In the sense, “burning out” means you’re overtraining.

In the text Essentials of Strength and Conditioning, a common cause of overtraining is cited as “a rate of progressive overload that is too high. That is, increasing either the volume or intensity (or both) too rapidly over a period of several weeks or months with insufficient recovery can result in greater structural damage and, potentially, overtraining (OTS)…A mistake in the prescription of any acute program variable could theoretically contribute to OTS if it is consistently repeated over time. This can often occur when highly motivated athletes use a high volume of heavy training loads with high training frequency and take limited rest to recover between workouts.”

The red portion in the above chart is what overtraining can look like. When you consistently disrespect the balance between strain and recovery for a prolonged period of time, the body will no longer be able to adapt to the stress of training. No adaptations, no improvement. Suddenly, that “No Days Off” mindset has put you in a position where you have no choice but to rest and recover. If you’re lucky, you’ll realize this before you suffer a significant injury, but it still may take weeks or months to fully recover from overtraining.

The initial warning signs that you’re on the road to overtraining include decreased performance and increased fatigue.

Over time, more abnormal symptoms can appear, including waking up in the middle of night, being unable to fall asleep at night, a significantly raised resting heart rate, recurring headaches, reduced appetite, irritability, and/or a lack of competitive drive.

If you find yourself in this position, be open to taking a week or two off to wind that torch back up. Otherwise, you are only burying yourself deeper! A week “off” doesn’t necessarily mean lying in bed all day. It just means significantly decreasing the intensity of your training and allowing your body an honest opportunity to recover. If you think you are overtraining, you should also talk to your coach, athletic trainer and/or doctor about the topic.

How can we avoid overtraining in the first place?

One easy way is to record and monitor your fatigue levels during workouts using Rate of Perceived Exertion, or RPE.

Using a scale of 1-10, 10 being the hardest session you’ve ever done and 1 being a super easy, barely-break-a-sweat workout, you assign a score to each training session shortly after you’ve completed it (ideally immediately after you’ve completed it).

As a general rule of thumb, if you rate a session as an 8 or higher, hold back for a day or two before hitting another hard session. Ultimately, if you were to plot your RPEs on a chart, there should be consistent ups and downs over time.

Another more scientific way of recording and monitoring your fatigue is through Heart Rate Variability (HRV). HRV can be a great tool for understanding where your resting heart rate stands each morning. This is done by a device (Heart Rate Monitor) measuring your heart rate, and an App on your phone recording the variability within the beats. The more rhythmic your heartbeat, the better recovered you are. It’s actually really simple, and HRV devices are quite affordable.

As an athlete, your goal is continuous, sustainable improvement. Be honest when you feel you may be veering into overtraining. If you do your own program, allow yourself a couple days off and see if your symptoms improve. If you follow a program from a coach, be up front about your symptoms and discuss scaling things back for a bit. If they’re worth their salt, they’ll be grateful for your honesty and willing to find a solution.

Photo Credit: martin-dm/iStock, BMJ

References:

Budgett, R. (1998). “Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndrome.” British Journal Of Sports Medicine, 32(2), 107-110.

Koutedakis Y, Budgett R, Faulmann L. “Rest in underperforming elite competitors.” Br J Sports Med 1990;24:248– 52.

Soligard, T., Schwellnus, M., Alonso, J., Bahr, R., Clarsen, B., & Dijkstra, H. et al. (2016). “How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury.” British Journal Of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1030-1041.

READ MORE: