How To Help Your Athletes Reflect On Their Performance

Children look to their parents for signs of approval, recognition, and love when they perform any new skill.

This approval transfers to coaches when the child starts playing an organized sport.

The child learns that the unconditional love and admiration they received from their parents are missing from the coach, but they can still get recognition, even if it is cadged with feedback on end. Sometimes, if they feel that they cannot perform to the group’s expectations, they may seek attention in other ways: being the team clown or sitting on the floor and refusing to join in.

These are normal behaviors in children.

Our job as coaches and parents is to help the child develop into an emotionally intelligent, self-aware, and self-confident individual who can function in society and perform in the sporting arena (if they so choose).

The athlete goes out and plays on the pitch and has to learn how to interact with teammates, perform their skills, and adapt to the opposition. If they can’t do that without the coach giving them continuous instructions, the coach has failed to prepare the child for the game.

Developing Self-Reflection Skills

Coaching is a balance of directing and asking. We sometimes ask the athletes,

- Put your hands here

- Play X

- Where were your hands?

- What play works best against that formation?

If we direct then, we lose valuable information from the athlete and stunt their growth. If we ask questions, we can confuse the athlete or take longer to learn a lesson. It is tempting to tell beginners what to do, but we need to get the athletes thinking for themselves at a young age.

When coaching gymnastics, I explain the headstand by showing that the two hands form the base of a triangle and the head is the top of the triangle (directing/ instructing). The gymnasts then practice and inevitably topple over. Over half of the athletes will have inverted the triangle by moving their hands in front of their heads. Another third will have hands and their head on a straight line. I then ask them, ‘Did you make a triangle shape?’

The answers vary, so I get them to do it again, thinking about the triangle shape. We use lines on the floor to help: hands behind the line, head in front. Yet, they still make mistakes at the beginning. The point is that I am teaching them to pay attention to only one part of a skill. Being upside down and trying to balance is distracting them from this. It’s a start. The feedback loop is then initiated that should help them learn any new skill:

- Listen/ Observe

- Experiment

- Pay attention to specific cues

- Check self

- Practice more.

Competition Evaluation and Goal Setting

As the athlete grows, they often leave their support networks behind: their high school coach, parents, and school friends. The ability to self-reflect becomes more critical as the young adult has yet to form a new support network or might be fighting for a place in the team and doesn’t want to ask the coach for feedback.

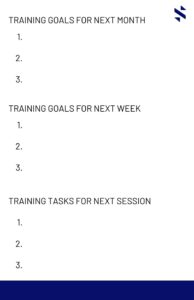

I use a simple form to help structure the athlete’s thought processes and turn them into constructive action. It involves three steps (note, this is for teenage athletes and would be too much for young children and is only introduced after some simple ask/reflect questions).

Step 1: Write down five things that you did well in the last game/ match.

Step 2: Write down three things that could improve

You will notice that I start with what went well and that more of those than what can be improved. We want confident athletes, which helps reinforce the fact that they will have done some good things even in a loss.

I never use the terms ‘Positive/ negative feedback’ because all thinking is useful, and can learn from mistakes. Note the dotted line on the form.

Step 3: Write down 3 training goals for the next month that will help you improve the areas you can improve.

Step 4: Be more specific and break down the larger goals into manageable tasks for next week.

Step 5: Be even more specific and write down two drills or exercises with sets and repetitions that you will put into your next training session.

You now have a positive, specific, and measurable action to help you get better.

Step 6: Throw away the bottom of sheet one (below the dotted line): there is no point dwelling on mistakes once you have a plan to improve

Use the top 5 points as a reminder of your past success and review it regularly.

I have found this process changes the mindset of the athlete and helps them transition ideas into action. They have to fill in the boxes and think hard about their game. They start to take control of their own improvement.

You may not have to do this after every game, but after big games, or once a month might help.

Summary

There are many ways to get better at sport, but thoughtful, deliberate practice, is essential at some point. Coach feedback and technology, such as film reviews, are important but should not be exclusive.

By helping your athletes reflect on themselves, you are helping create independent and adaptable thinkers who can perform in the sporting arena successfully and confidently.

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

How To Help Your Athletes Reflect On Their Performance

Children look to their parents for signs of approval, recognition, and love when they perform any new skill.

This approval transfers to coaches when the child starts playing an organized sport.

The child learns that the unconditional love and admiration they received from their parents are missing from the coach, but they can still get recognition, even if it is cadged with feedback on end. Sometimes, if they feel that they cannot perform to the group’s expectations, they may seek attention in other ways: being the team clown or sitting on the floor and refusing to join in.

These are normal behaviors in children.

Our job as coaches and parents is to help the child develop into an emotionally intelligent, self-aware, and self-confident individual who can function in society and perform in the sporting arena (if they so choose).

The athlete goes out and plays on the pitch and has to learn how to interact with teammates, perform their skills, and adapt to the opposition. If they can’t do that without the coach giving them continuous instructions, the coach has failed to prepare the child for the game.

Developing Self-Reflection Skills

Coaching is a balance of directing and asking. We sometimes ask the athletes,

- Put your hands here

- Play X

- Where were your hands?

- What play works best against that formation?

If we direct then, we lose valuable information from the athlete and stunt their growth. If we ask questions, we can confuse the athlete or take longer to learn a lesson. It is tempting to tell beginners what to do, but we need to get the athletes thinking for themselves at a young age.

When coaching gymnastics, I explain the headstand by showing that the two hands form the base of a triangle and the head is the top of the triangle (directing/ instructing). The gymnasts then practice and inevitably topple over. Over half of the athletes will have inverted the triangle by moving their hands in front of their heads. Another third will have hands and their head on a straight line. I then ask them, ‘Did you make a triangle shape?’

The answers vary, so I get them to do it again, thinking about the triangle shape. We use lines on the floor to help: hands behind the line, head in front. Yet, they still make mistakes at the beginning. The point is that I am teaching them to pay attention to only one part of a skill. Being upside down and trying to balance is distracting them from this. It’s a start. The feedback loop is then initiated that should help them learn any new skill:

- Listen/ Observe

- Experiment

- Pay attention to specific cues

- Check self

- Practice more.

Competition Evaluation and Goal Setting

As the athlete grows, they often leave their support networks behind: their high school coach, parents, and school friends. The ability to self-reflect becomes more critical as the young adult has yet to form a new support network or might be fighting for a place in the team and doesn’t want to ask the coach for feedback.

I use a simple form to help structure the athlete’s thought processes and turn them into constructive action. It involves three steps (note, this is for teenage athletes and would be too much for young children and is only introduced after some simple ask/reflect questions).

Step 1: Write down five things that you did well in the last game/ match.

Step 2: Write down three things that could improve

You will notice that I start with what went well and that more of those than what can be improved. We want confident athletes, which helps reinforce the fact that they will have done some good things even in a loss.

I never use the terms ‘Positive/ negative feedback’ because all thinking is useful, and can learn from mistakes. Note the dotted line on the form.

Step 3: Write down 3 training goals for the next month that will help you improve the areas you can improve.

Step 4: Be more specific and break down the larger goals into manageable tasks for next week.

Step 5: Be even more specific and write down two drills or exercises with sets and repetitions that you will put into your next training session.

You now have a positive, specific, and measurable action to help you get better.

Step 6: Throw away the bottom of sheet one (below the dotted line): there is no point dwelling on mistakes once you have a plan to improve

Use the top 5 points as a reminder of your past success and review it regularly.

I have found this process changes the mindset of the athlete and helps them transition ideas into action. They have to fill in the boxes and think hard about their game. They start to take control of their own improvement.

You may not have to do this after every game, but after big games, or once a month might help.

Summary

There are many ways to get better at sport, but thoughtful, deliberate practice, is essential at some point. Coach feedback and technology, such as film reviews, are important but should not be exclusive.

By helping your athletes reflect on themselves, you are helping create independent and adaptable thinkers who can perform in the sporting arena successfully and confidently.